In 2015, law enforcement secretly acquired surveillance video image analysis software from the Israeli company Briefcam. For eight years, the Ministry of the Interior concealed the use of his tool, which enables facial recognition

This has become a habit. On Tuesday, November 14, just as in the previous edition, Gérald Darmanin inaugurates the Milipol exhibition at the Villepinte Exhibition Centre (Seine-Saint-Denis). Dedicated to the internal security of states, this exhibition is a global showcase for companies often unknown to the general public. Briefcam is one such company, an Israeli firm specializing in the development of algorithmic video surveillance (VSA) software. Through artificial intelligence, this technology analyzes images captured by cameras or drones to detect deemed “abnormal” situations.

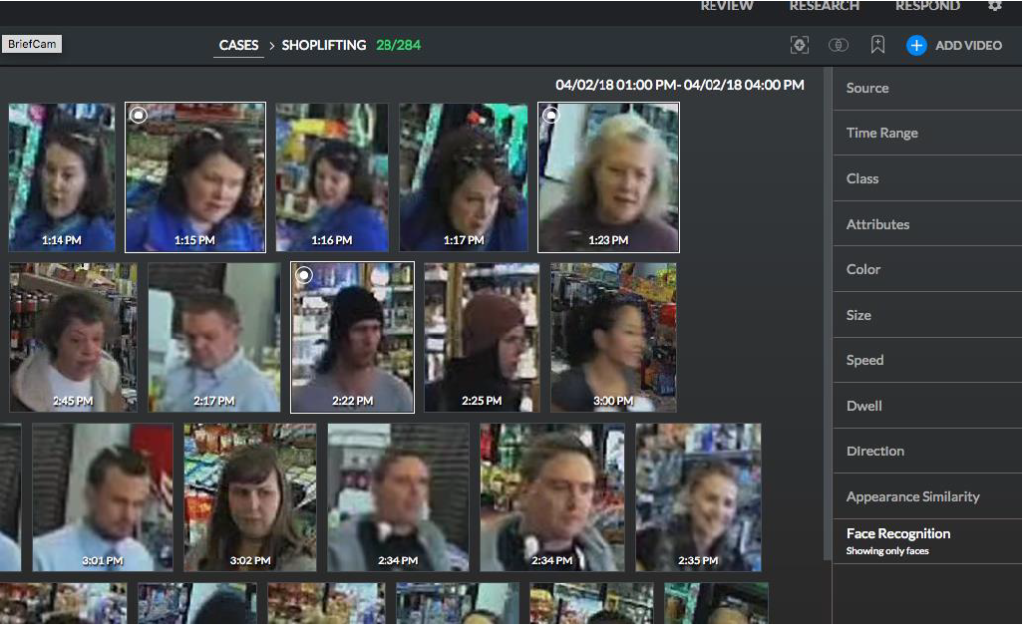

Until last May, the national police were only allowed to use VSA in very rare cases. However, with the approach of the Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games, the government managed to pass a law in parliament authorizing its large-scale experimentation by the national police until March 31, 2025. Faced with privacy risks, the members of parliament nonetheless prohibited the use of facial recognition, which identifies a person in images based on facial features. This is an extremely intrusive tool that some software marketed by Briefcam allows activation in a few clicks. And it’s a tool that Gérald Darmanin’s services are familiar with.

Software deployed nationwide

According to internal documents from the Ministry of the Interior obtained by Disclose, law enforcement has been using Briefcam’s systems since 2015, in utmost secrecy. The software in question, called “Video Synopsis,” can track a person across a network of cameras, for instance, by the color of their sweater. It can also track a vehicle using its license plate or analyze several hours of video in just a few minutes. Briefcam’s slogan, acquired by the photo giant Canon in 2018: “Transforming video surveillance into active intelligence.”

Eight years ago, the Seine-et-Marne Departmental Directorate of Public Security (DDSP) was chosen to experiment with the Israeli software. Two years later, in 2017, the application was deployed more widely. Police services in Rhône, Nord, Alpes-Maritimes, and Haute-Garonne were also equipped. As well as the Interministerial Technical Assistance Service (SIAT), a police unit responsible for infiltrations, wiretapping, and monitoring serious crime.

« Il semble préférable de ne pas en parler »

Subsequently, it was the judicial police services, the police prefectures of Paris and Marseille, public security, and the national gendarmerie that were equipped with Briefcam’s software on dedicated computers. This massive installation was carried out outside the legal framework provided by a European directive and the French Data Protection Act.

Before using such intrusive technology offered by Briefcam, the Ministry of the Interior should have conducted an “impact analysis on data protection” and submitted it to an independent authority: the National Commission for Information Technology and Civil Liberties (CNIL). However, the Directorate General of the National Police (DGPN), under the direct authority of Gérald Darmanin, had still not conducted this impact analysis by May 2023. Nor did they notify the CNIL. Therefore, at the end of 2020, a police official suggested discretion: “Some services have the Briefcam tool, but since it is not declared to the CNIL, it seems preferable not to talk about it.” Or this message sent a few months later by another senior officer, recalling that “legally speaking (…) the Briefcam application has never been declared by the DGPN.”

Contacted by Disclose, the CNIL stated, embarrassed, that they “do not have elements to confirm or deny that the national police use Briefcam.” The DGPN did not respond to our questions.

Facial recognition option activated in a few clicks

Briefcam’s popularity among police services could be explained by the illegal use of one of its flagship features: facial recognition. This allows “detecting, tracking, extracting, classifying, and cataloging” a person based on their face, as explained by the company on its website. And to use it, it’s quite simple: just select “one or more faces” before clicking on “the facial recognition button displayed to the right of the playback area,” as indicated in the user manual (french version) transmitted to Disclose by La Quadrature du Net, an association defending rights and freedoms on the Internet. In a few clicks, it’s done

This possibility offered by Briefcam has indeed been highlighted as a real “plus” by the service in charge of technological tools within the DGPN. In an email sent in November 2022, a high-ranking police officer explains that the software has “features such as license plates, faces,” but also “more ‘sensitive’ features” such as “distinguishing gender, age, adult or child, size.” Finally, he specifies that certain modules of the application allow “detecting and extracting people and objects of interest afterwards” but also conducting “real-time” video analysis.

The potential use of facial recognition worries within the institution itself. In a “legal status update” dated May 2023, a cadre of the National Directorate of Public Security (DNSP) alerts their hierarchy: “Regardless of the software used (especially Briefcam), it is prohibited to use any face matching or facial recognition device,” outside strict legal boundaries.

Briefcam equips municipal police in nearly 200 towns

In France, facial recognition is only authorized in rare exceptions. It can be part of judicial or administrative investigations “punishing a disturbance to public order or an infringement on property, individuals, or state authority,” as highlighted in an April 2023 parliamentary report. In such cases, investigators can rely on the TAJ, the judicial antecedent processing, which, in 2018, contained about eight million records with photos of faces. The other case where facial recognition is authorized concerns the fast passage system at external borders (Parafe), which are security gates comparing the faces of travelers to their biometric passports.

However, according to a well-informed source within the national police, Briefcam’s facial recognition is actively used. Without control or judicial requisition. “Any policeman whose service is equipped can request to use Briefcam by transmitting a video or photo,” assures our interlocutor. The DGPN did not respond to Disclose’s inquiries on this matter. As for Briefcam, its sales director in Europe, Florian Leibovici, remains vague: “This type of client remains confidential, and we have very little information on how our tool is used.”

The company Briefcam, founded in 2008 by three teachers from the School of Computer Science and Engineering at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, not only equips French law enforcement. According to a confidential presentation document obtained by Disclose, Briefcam has assisted police services in Israel, the United States, Brazil, Taiwan, and Singapore. According to the independent research center Who Profits, Briefcam is also used by the Israeli Ministry of Housing to monitor Palestinian areas of East Jerusalem occupied by settlers.

In France, “more than a hundred cities” have equipped their municipal police with the Briefcam application, according to its representative in Europe, Florian Leibovici. This is notably the case in Nice, Roanne, Aulnay-sous-Bois, Perpignan, or Roubaix. Briefcam’s algorithms also scrutinize visitors to the Puy du Fou amusement park and soon, the elected officials of the National Assembly. This deployment makes the company one of the leaders in the French market.

On the Ministry of the Interior’s side, there seems to be no willingness to stop using the Israeli software anytime soon. Before summer, the Central Directorate of Public Security (DCSP) approved the renewal of the Briefcam license for the departmental security services of Rhône, Nord, and Seine-et-Marne. These licenses expire at the end of 2023. To continue using them, the police hierarchy dipped into the “drug fund.” A fund, fueled by seizures related to drug trafficking, which should normally serve the fight against drug trafficking and addiction prevention.

Investigation: Mathias Destal, Clément Le Foll, Geoffrey Livolsi

Editor: Pierre Leibovici [end]

Leave a comment